Enrico De Angelis discusses the controversiality of horror images in his essay “The Controversial Archive: Negotiation Horror Images in Syria”. He examines different perspectives on the effects of such widespread and often uncontextualized horrific content. Emily Wills discusses the same issues in light of the photographs of three-year-old Alan Kurdi’s dead body in her essay, “Alan Kurdi’s Body on the Shore”.

Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the internet has become flooded with images of violence mostly produced by young, local citizen photojournalists. This vast collection of images is what De Angelis calls the “controversial archive”. The archive is controversial because the images that circulate on the public internet and social media are often given very little context. Due to policies of local media organizations, the desire to remain anonymous themselves, and unprofessional circulation on social media, the photographer's names as well as the photographed people’s names often are not included with the photographs. This creates what De Angelis calls, “orphan images”; images with no known origin.

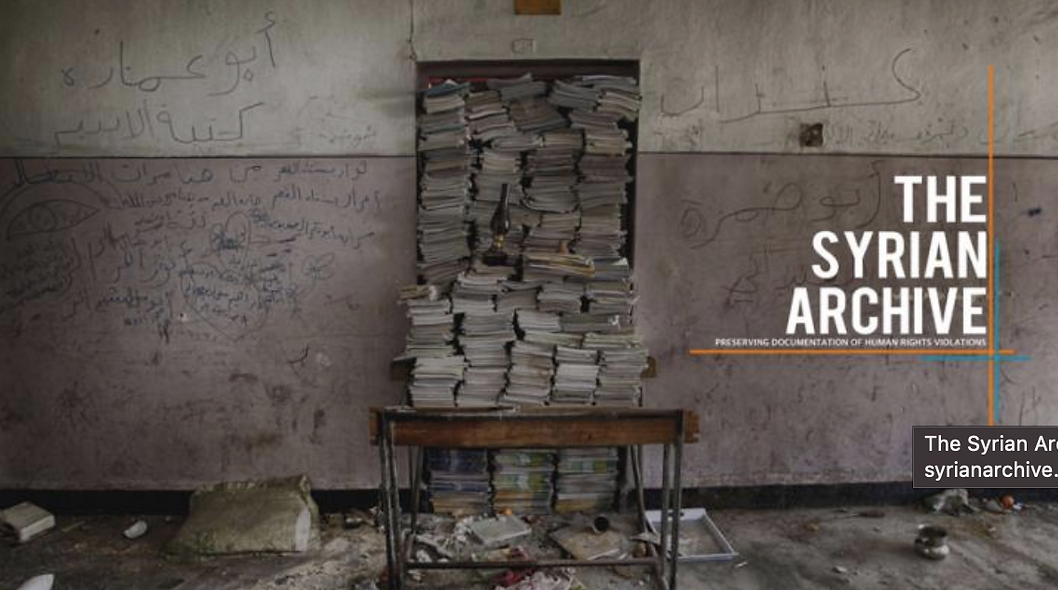

The Syrian Archive is an organization that is attempting to deal with the global archive of uncatalogued information. I found this organization similar to forensic architecture because both deal with the effects of the dissemination of information, however in different ways. Unlike forensic architecture, which tries to demonstrate the "truth" of the situation, often in times of fake news narratives and alternating perspectives, The Syrian Archive deals with the problem that no meaning, names, or stories are associated with photos and videos at all. Their organization attempts to catalog and trace the history of photos from Syria that circulate the web in order to inform people and humanize these pictures.

Unlike other situations such as Palestine, where the dissemination of images lends itself to tight state control over the visual field by way of a repudiation script that paints a very specific anti-Palestinian narrative (see my last blog post for more on this), the dissemination of horror images in Syria has done the opposite. Here, there is a lack of control on all ends of the field of vision. The conflict is most definitely not invisible. Instead, the archive creates an “identificatory gaze”; a viewing of images that normalizes violence by reducing the subject to a predetermined meaning.

The case of the Alan Kurdi photographs exemplifies the international power that horror images hold. Though these specific photos have stark differences from the majority of pictures we see of violence. Wills notes that instead of the typical realism and gore that is usually seen in Arab activist documentation, the photos of Alan Kudri's body are beautiful, calm, and peaceful. The colors are bright, he looks like he could be sleeping, and he is dressed in a red t-shirt, shorts, and sneakers -- the perfect victimization for Western action.

The photo of Alan Kurdi in September 2015 captured by Nilufer Demir.