A frame from the video of King's beating captured by Holliday. This was one of the frames likely shown to the jury. One could think that this grainy picture may speak for itself, but it is clear that photos do not do that, and vision is by no means the same as sight/ truth.

These biased judgments are what Judith Butler considers "white paranoia"-- the circumscription of a black body as dangerous before any gesture or threat of violence. The defense attorneys showed frames from the video in an attempt to claim that King was a threat to the police. Because the jury is "seeing" these clips through a racially saturated field of visuality, they can judge that King's movements to block the repeated beatings were gestures of violence. In reality, what the jury did was no sight at all; their vision was so tainted by white supremacy and paranoia that they were able to "read" the visual evidence accordingly. In fact, the evidence was not even necessary for the jury to come to their decision as they had already decided just on seeing the color of King's skin that he was guilty. Butler calls for an aggressive counter-reading of this evidence and an aggressive reading of the racist schema that orchestrates and interprets it. White paranoia is ingrained in our social and judicial systems, so breaking it down is not just a matter of finding a few officers guilty but one of finding the whole system accountable.

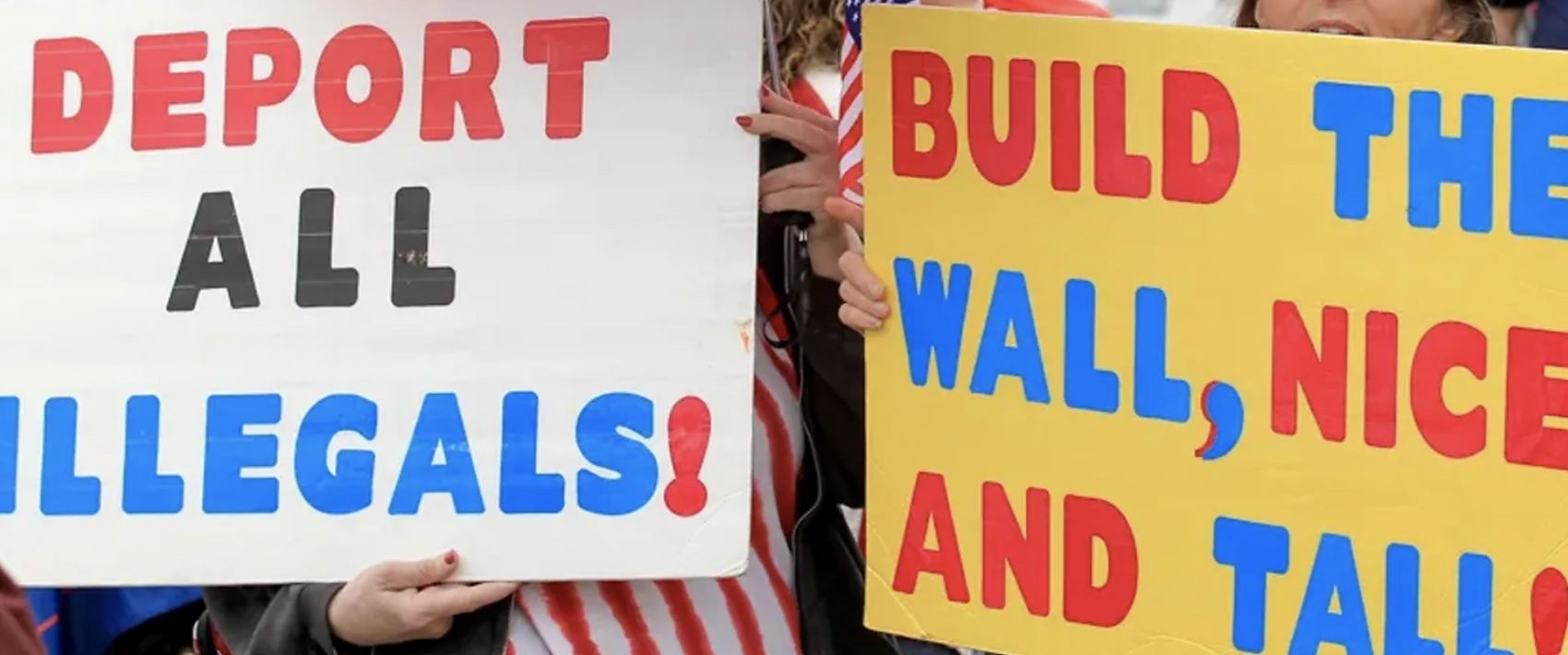

Photos taken from 2018 Trump rallies. These posters reading "deport all illegals!" and "build the wall, nice and tall!" demonstrate the racism and violence that occurs with white paranoia.

To do so, we must look into the history of the United States to find the root of these biases. Elsa Dorlin's article describes the principle of self-defense and its historical links to U.S. constitutionalism and the racist society we live in today. According to Dorlin, the right to armed self-defense has been integral to American legal culture since it was a British colony. Originating from the Anglo-Saxon belief in the natural right to self-preservation, as Locke proposed, the right to bear arms initially gave citizens the right to defend themselves against monarchy and oppression— the defense of property as if it were themselves. However, in the United States, the right to bear arms takes more forms than just combatting monarchy and oppression. Using arms to exterminate indigenous nations and refuse British control makes self-defense a fundamental element of the United States' colonial, racial, and social history. It is interesting to note on account of the extermination of indigenous nations that this falls under 'self-defense.' This is because the right to self-defense is intrinsically colonialist; U.S. citizens were seen as frontiersmen defending themselves against any threat to push back the frontier they thought to have jurisdiction over.

A painting depicting the 1863 Bear river massacre in which around 400 Shoshone people were killed at the hands of American pioneers. This picture demonstrates the use of arms in the extermination of indigenous nations to "defend any threat to push back the frontier."

The right to bear arms has paved the way for vigilantism and the rise of vigilante committees. Vigilantism is the practice of preventing, investigating, and even punishing criminal offenses without legal authority. Many believe vigilante committees came from undeveloped political institutions and the need to enforce justice. However, Dorlin argues that this is wrong. As supported by Alexander Barde's book "Histoire de Comités de vigilance aux Attakapas" in 1861, vigilantism is incredibly racialized and part of a process of rationalizing society. Barde's writing and work are a record of colonial violence and racism in the name of vigilantism and self-defense. Their goal was simple; the vigilantes wanted to 'purify' the country.

Vigilantism could be seen as the birthplace of "white paranoia." It is a system in which the minority is assumed guilty before any proper judgment. Vigilantism both institutionalizes and weaponizes white supremacy. It is impossible to talk about vigilantism without discussing the history of lynchings in the united states. Under the pretext of defending the honor of white women, vigilantes performed lynchings and all other acts of racism out of the fear (or paranoia) of black bodies. Women were seen as property and therefore gave grounds to be defended by white men (even when the women themselves did not want to accuse the men of assaults that did not occur or did occur but at the hands of white men). White supremacists constructed the myth of the black rapist to defend the white race and the idea of black bodies as inherently violent lives within our social and legal systems today.

Armed counterprotesters and a police officer stand watch on the perimeter of a Black Lives Matter protest in Provo, Utah, on July 1, 2020. The presence of police shows that vigilantes don't arise from an absent or weak government. Still, these armed men are often present in circumstances where they feel their white superiority is challenged.