A photo of two NYPD officers using their stop-and-frisk policy on a black teenager (2016).

The space of appearance refers to the cracks in the society of control; in this case, these cracks are moments in which people claim the right to look and white supremacy becomes visible. Mirzeoff refers to it as the society of control because it is quite literally what controls us. Through policing and social law, institutions actively control and order their citizens. In practice, this becomes incredibly racialized. For example, the stop-and-frisk policy allows officers to stop, question, and even physically search any person about which they have a suspicion. This practice comes from a history of controlling the movements of the enslaved. In modern society, this same control is enacted through racist codes that police use to target non-white citizens. Specific codes that target bodies and bodily practices such as loitering, public drinking, and drug use allow authorities to use their discretion to stop anyone who they may feel is in possible violation of one of these codes. Due to white paranoia and racism, black people are often the targets of these stops and, in many cases, are victims of unjust violence that follows. A space of appearance is created when people acknowledge this control and then publicly, actively, and persistently claim the right to look at it.

The space of appearance has two forms: kinetic and mediated forms. The kinetic manifests in real spaces: protests, marches, physical acts of resistance, and activism. The mediated form takes place online through documentation and social media. The black lives matter movement has successfully created a space of appearance by using both forms interdependently.

Black lives matter represents a shift from simple street protests that aim to ask authorities for a specific change to performances that invoke what anti-blackness would look like. These protests evoke extreme emotions in participants and viewers that other forms cannot do. Mirzeoff discusses a slogan that has become principal to the movement: "hands-up, don't shoot." In any black lives matter protest, you can guarantee that this will be one of the primary chants of the crowd, generally accompanied by people raising their hands over their heads. This originated after Michael Brown was shot by a police officer on August 9, 2014, in Fergusen, Missouri. Witnesses claim that Brown had his hands up, indicating vulnerability and submission when shot. While this gesture originates from the specific case of Brown's murder, "hands up, don't shoot" captures the innocence and vulnerability of the many other victims of police brutality. In light of such tragedy, there is typically a call from the media for closure, healing, and moving on, but the "hands up, don't shoot" pauses the action at a crucial and almost uncomfortable moment. This discomfort forces anyone witnessing to assume that any reasonable person would not shoot– but the cops still did.

Photo from a Black Lives Matter protest where protesters are using the "hands up, don't shoot" slogan.

Another example of the kinetic form of the space of appearance that Mirzeoff investigates is the die-ins: a form of protest in which the participants lay down and simulate being dead. Like "hands up, don't shoot," die-ins are conducted to emphasize the defenseless and harmless nature of the victims. Protesters for many different causes have been using die-ins to force awareness upon passers-by. Mirzeoff examines that die-ins represent a counter-body politic by creating a collective body that demonstrates an entire population of people to which the system has failed.

Scenes from Black Lives Matter Die-In in Sacramento, California (2020)

The digital era has allowed movements like black lives matter to create as much momentum as they have. Not only has the digital age allowed for citizen journalism on entirely new levels, but it also makes a profound sense of repetition and persistence vital in growing the space of appearance. Mirzeoff argues that repetition does two important things. First, it instills a sense of urgency for the cause. When it becomes impossible to scroll through social media without seeing #blacklivesmatter, and when cases of police brutality become increasingly visible, it becomes impossible to watch without the feeling that something must be done. Second, it creates space for viewers to overcome the initial shock of seeing mass protests or horrendous cases of police brutality and to think critically about what has happened.

This photo is of the #blacklivesmatter feed on "blackout Tuesday." On June 2, 2020, a collective action to protest police brutality occurred. Social media users created a "blackout" in which nothing else could be posted except for BLM content, specifically a black square. Intended as a sign of solidarity, this soon became problematic because it began to drown out all educational news and helpful information regarding protests under the hashtag. Regardless, this poses an example of how inescapable the movement is. If you were on social media, you were forced to know and see that black lives matter.

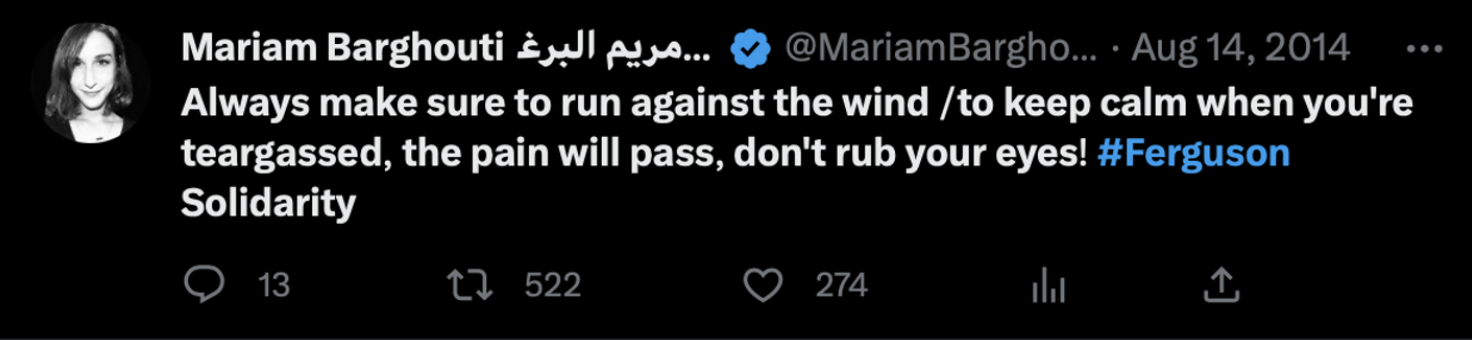

The digital side of the movement also allows for what Mirzeoff calls a "digital co-presence," the prominent online community created as a byproduct of hashtags and Twitter threads. This digital co-presence provides a sense of collective solidarity and "freedom of appearance," where people make themselves visible to one another. An example of this is the relationship between Palestine and Black Lives Matter. Shortly after resistance began in Ferguson, Palestinians joined the Black Lives Matter online community with advice on handling counterinsurgency and staying safe during protests with active state resistance. This demonstrates that the digital era allows for an even larger scale, global space of appearance.

Palestinian activist Mariam Barghouti tweeted words of solidarity and advice during one of the most dangerous nights of the protests in Ferguson.