Mbembe references Faucault’s concept of biopower numerous times in the essay as it is probably the most similar to MMbembe'stheories of Necropower and Necropolitics. Biopower is the exercise of power over life or that domain of life in which power has taken full control. Biopolitics refers to the state's execution of biopower. Biopolitics theoretically is a very beneficial force. State-mandated vaccinations are a prime example of how biopolitics can play an important role in preventing disease and reducing mortality rates… quite literally promoting life. However, biopolitics strips individuals of their bodily autonomy. Abortion laws and forced sterilization are just two examples in which biopolitics can be used to instill power and control over individuals' bodies (note: vaccinations do this too, but in a much less harmful way). Biopolitics is also inherently discriminatory. Because the sovereign power (usually the state) has the right to decide who specifically receives this “right to live” and who does not. Mbembe argues that “Biopower” is not sufficient enough for describing situations in which figures of sovereignty make the murder of their enemies their primary goal. His theories on necropolitics and necropower arise as a solution for this insufficiency.

Abortion laws are just one example of ways in which states can exercise biopower. This photo is from the Boston Women's March in 2021. The poster reads "Keep your laws off my body". This exemplifies how angry these types of laws that infringe on bodily autonomy make populations.

Both necropower and biopower manifest themselves through racism that is entrenched in Western political thought. Racism is used as a technology to permit the exercise of biopower and necropolitics by splitting and dividing the population into subgroups thought to be deserving of differential treatment by the state. This splitting and dividing paves the way for what can be known as “states of exception", a term proposed by Giorgio Agamben to describe places within democratic countries– both physical and theoretical– in which the rule of law is put on hold and the extralegal exercise of torture, detention, and surveillance is performed.

This is an art installation by Richard Barnes titled "state of exception". It includes various installations created by objects found in the desert around the US - Mexico Border. This installation aims at demonstrating the state of exception that those attempting to cross the border have been placed in. Irregular migrants are put within states of exception within democratic countries because both citizens and the government do not see them as equals within society. Because of this, they are often faced with disproportionate violence.

Through the negative differentiation of certain populations, otherwise, democratic states are able to place these people in states of exception and either flat out-execute them– or revoke the inhabitants of their political and social statuses, reducing them to what can also be considered a "bare life" or strictly survival. One way in which states can more easily get away with this is through the industrialization and dehumanization of death. An example that Mbembe uses to describe this is the gas chambers used in Nazism. This method of mass killing is representative of the shift away from public executions (meant to instill a fear of death as a means of controlling populations) to procedural executions that are technical, impersonal, and rapid. Mass murder such as those in the gas chambers, aims at efficiency: the disposal of large numbers of victims as fast as possible. The depersonalization allows for an image of 'civilization' of murder. Taking the focus away from the individuals killed paints the killings as a necessary step towards a political goal. It allows for the state of exception to exist, untouched, within the walls of a democratic state.

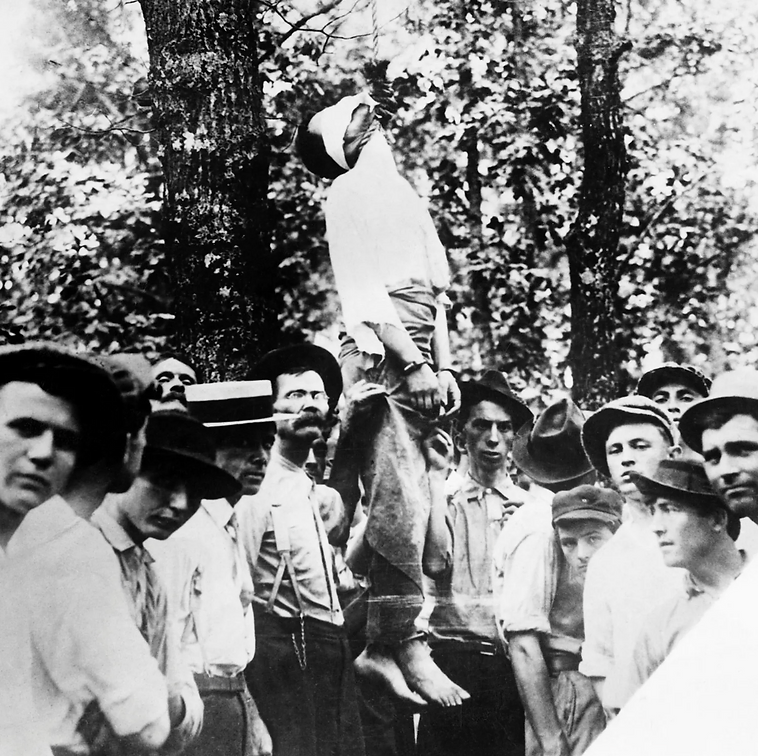

Mass graves of the holocaust (left) compared to Lynchings of African Americans in the USA (right). This demonstrates a shift from public murders to industrialized, and 'efficient' methods of mass killing.

It is very important to note that the states of exception as seen in Nazism and Stalinism have their origins in colonialism and slavery– more specifically the structure of the plantation. Slavery can be seen as one of the first instances of biopolitical experimentation and the plantation structure is representative of the state of exception. Within the plantation system, the humanity of the slave is stripped to 'bare life'. They are kept alive solely because their masters need to use them as tools. Their life becomes a form of commerce and their masters hold the power to decide if they live or die.

The practice of dehumanization and negative differentiation as a means to commit mass slaughter of groups of people stems directly from colonialism. In the eye of the conqueror, colonies without an organized "state" to impose reason, were considered rightful places of violence. Any native life was considered 'savage' and 'animal' and the colonizer could kill at will with no necessary motive. The state of exception imposes this same colonial warfare within democratic states. Mbembe argues that the contemporary state of exception uses these same mechanisms and ought to be considered a colonial and racial matter.

This famous painting "American Progress" by John Gast is a representation of the cultural belief in 'manifest destiny' that encouraged American settlers to venture west into the "frontier". In the painting, it depicts Native Americans as uncivilized and running in fear, it gives the notion that the land is there to be taken and that they are "savages" that are there to be killed.

The state of exception conceives itself within colonialism and slavery but has taken different forms throughout history with the rise of technology. In the chapter of his book titled "The Becoming Black of The World", Mbembe claims that neoliberalism has created a world in which everyone is commodified by Silicon Valley and digital technology. He suggests that this creates a state of exception that is experienced by all human beings. Essentially, every human– regardless of race– becomes a slave to capitalism. Hence, the title "the becoming black of the world". To conclude Mbembe questions racism's role in modern and future society.