In simple terms, cyberwar is the use of computers to carry out deliberate, digital attacks on enemy states or organizations. It is crucial to note that although it is conceived online and through technology, cyberwar is most definitely a way of fighting that has devastating effects on real human lives. The roots of the term cyberwar come from fiction– making the reality of modern warfare all the more dystopian.

The motives of these attacks are wide-ranging. Often, cyberwar is used as a mechanism of self-defense and prevention against harm. An example of this is Operation Olympic Games, a sabotage attack on the Iranian uranium supply done by US and Israeli agencies. The attack was done by deploying viral malware known as Stuxnet and aimed to prevent President Ahmadinejad from building a nuclear bomb. Operation Olympic Games also exemplifies the inherent link between cyberwar and nuclear warfare.

Just like Operation Olympic Games, almost all cyber attacks have very strange and almost comical names; Operation Moonlight Maze, Operation Storm Cloud, Operation Titan Rain, Operation Grizzly Steppe, and Operation Buckshot Yankee are just a few examples. This is no coincidence but a very strategic use of rhetoric to sway public perception of these attacks. The reality is that many cyberwar attacks are acts of terrorism. The Russian occupation of the Chernobyl and Zaporizhzhia power plants last February and March are examples of how these attacks manifest themselves with real loss of human life. To take over the Zaporizhzhya, Russian troops violently forced their way through civilian infrastructure, destroying a school and apartment building. Once they finally reached the plant, Russian troops set it on fire– creating a sense of terror and “catastrophic proximity” to the Chernobyl disaster of 1986. Russian state media refused to call these attacks anything but “special operations” just as all the aforementioned cyberattacks were called. In her presentation in the Violence and Visibility symposium, Matvinyenko noted that refusing to call these attacks acts of war, opens up a space for unregulated war crimes.

Another element is at play when studying cyberwar and Russia's invasion of Ukraine: colonialism. Matvinyenko mentions the term nuclear colonialism in her piece which refers to the state and corporate oppression of indigenous people and land in order to maintain the nuclear production process. In the case of Russia, nuclear colonialism functions slightly differently as the word ‘colony’ itself doesn’t perfectly describe the relationship between Ukraine and the Soviet Union. Matvinyeko poses a new way of conceptualizing this by applying the concept of ‘internal colonization’. Russia’s act of nuclear terrorism still stems from a colonialist mentality towards the ex-territories of the soviet union and in addition to specific attacks of terrorism, the nuclear plants that exist within these ex-territories create radioactive leaks that harm the long-term physical health of the people. These leaks almost always go unreported by the state.

The Runit Dome, known by locals as "The Tomb" is a former US nuclear testing sight located on Runit Island in the pacific ocean. After time and erosion leaked radioactive chemicals into the surrounding air and water. This demonstrates nuclear colonialism as these leaks displaced many indigenous people from the Island.

Throughout all of this, a greater sense of disinformation and a very tightly controlled narrative is at play. The mystique surrounding cyberwar and the ability of states to fight proxy wars from afar allows for an immense gap in information that is up for media channels to fill. Unfortunately, as we have seen throughout this course, the media itself functions as a perpetrator and instigator of violence. The documentary compares the communication and reporting practices of Russia and Ukraine throughout the war. Ukraine takes a much more grassroots approach with many different voices reporting. Their focus is on casual, influencer-style social media reporting to elicit an emotional and relatable response. Russia does the opposite with formal, top-down communication entirely controlled by the state. Russian propaganda aims to devalue any news of war and spread two messages to its people: that Ukrainians are nazis and all media is a lie. Despite taking very different approaches, both sides demonstrate the huge role that mass media plays in narrative shaping and propaganda.

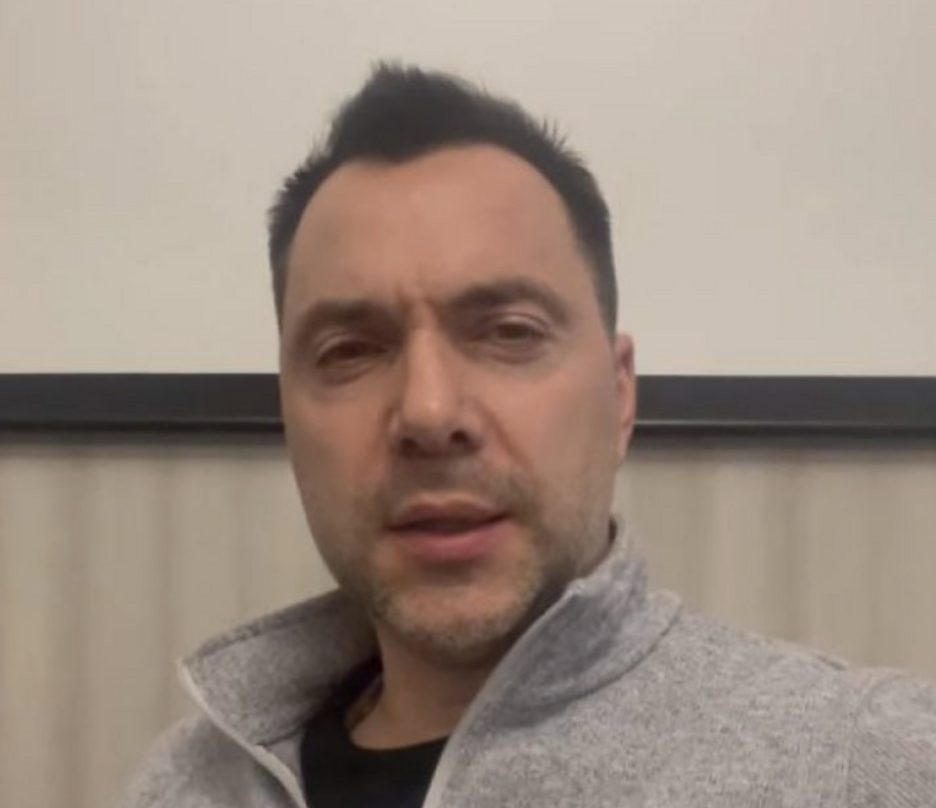

Here are photos of Solovslav (left), Putin's primary media person and state TV reporter, and Aristovich (right), Zelensky's main media support. Just by comparing the two images you can gain an understanding of the emotions and messages they are trying to evoke. Solovslav is very formal, powerful, and angry. While Aristovich is casual, recording from just his cell phone, wearing ordinary clothing.