SH*T WE CARE ABOUT

Issues and problems in media that deserve our attention.

Gallery

In 1835, tucked away in a treaty ceding southeastern Georgia Cherokee land to the U.S., the government agreed that the Cherokee people “shall be entitled to a delegate in the House of Representatives.” Last August, the largest federally recognized tribe finally took Congress up on this offer by appointing Kimberly Teehee, 51, to be its first U.S. House delegate.

The position isn’t Teehee’s only policy-making first. As the first senior policy adviser for Native American affairs in the White House Domestic Policy Council, she spearheaded the provision in the 2013 Violence Against Women Act reauthorization that lets tribal courts prosecute non-Indians who commit certain domestic-violence crimes on Indian lands. Over half of American Indian/-Native Alaska women have experienced sexual violence. “Tribes, like other jurisdictions, should have the ability to prosecute crimes committed on their lands,” she says, “making sure American Indian women have the same protections that women have in this country.”

Teehee is still waiting to be seated in Congress, where, like the delegate from D.C., she would be non-voting. But the symbolism of her presence would be strong, she says, as “an extra voice in the room” for her tribe and all others. —Olivia B. Waxman

Growing up Sikh in San Antonio, Simran Jeet Singh felt “highly visible yet entirely unknown,” he says. He was a high school senior when a streak of hate crimes against Sikhs swept the U.S. in the months after 9/11, and he realized that “ignorance is actually a matter of life and death.” He’s turned that drive into a career as a scholar and advocate for religious freedom. On his podcast Spirited, he interviews prominent figures about spirituality, and he has a regular column for Religion News Service. Notably, he’s written about the idea of “religious supremacy.” Just as white supremacy is a dangerous thread in American life, he argues, so is the idea that one religion is superior. For Singh, 35, religious equality requires challenging the assumption that Christianity is the default. “Then,” he says, “we can actually create an even playing field for people of different traditions.”

On Aug. 25, he’ll release a children’s book, Fauja Singh Keeps Going, the true story of a Sikh man who was the oldest person to run a marathon. “This has been my dream,” he says. “Growing up, we never saw a Sikh character in a children’s book.” But his children will. —M.C.

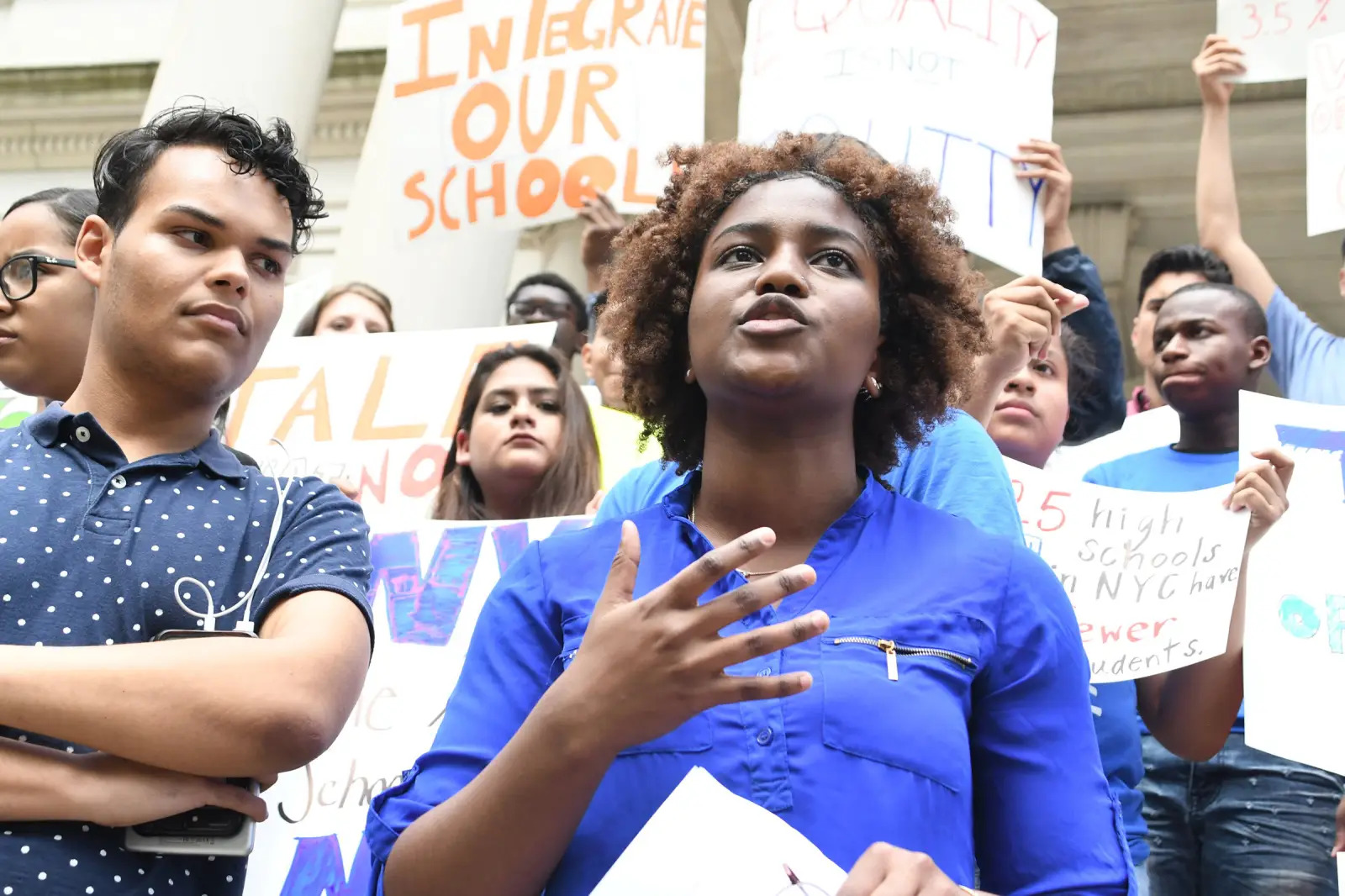

Nearly 66 years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public education unconstitutional, more than half of the nation’s students still attend largely segregated school districts. In New York City, one of the country’s most segregated school systems, students are leading the fight to change that.

Nelson Luna and Whitney Stephenson, both 19, founded Teens Take Charge at their public charter high school in 2017 to campaign for integration. Since then, Teens Take Charge activists from more than 30 high schools have led walkouts and a City Hall sit-in, protesting the uneven distribution of resources in the system and the admissions process for the city’s specialized high schools, which enroll mostly white and Asian students.

Now first-generation college sophomores, Luna and Stephenson are still involved in that advocacy, though a team of current high school students, along with fellow student-led activist group IntegrateNYC, have pushed the movement forward. This spring, both groups are planning a citywide school boycott, echoing a 1964 anti-segregation boycott by about 460,000 New York City students.

“Although it may look different in this era,” Stephenson says, “it’s still school segregation.” —K.R.

The roughly 437,000 U.S. children in foster care are more likely to drop out of high school compared with peers who live with family, and children who age out of the system are more likely to face homelessness, unemployment and incarceration. Foster care, while designed to help children in need, also exacerbates existing inequalities: poorer families are more likely to have a child removed from the home, and many advocates argue that’s because the child–welfare system scrutinizes signs of poverty, labeling it child neglect.

William C. Bell aspires to an America with as few children in foster care as possible. As president and CEO of Casey Family Programs, Bell, 60, was one of the strongest advocates for the Family First Prevention Services Act, landmark bipartisan legislation that aims to keep more families together. The law, which took effect in October, allows states to use federal funding to help struggling parents before resorting to putting children in foster care. “If we can get more children being raised in a family-like setting, either with their parents or extended family,” Bell says, “it bodes well for what happens in this country in the long run.” —K.R.

The Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) began in the 1990s as a collection of Florida-based farmworkers organizing to fight long-standing labor abuses. Lucas Benitez, 44, one of the co-founders, tells TIME via translator that the CIW’s main goal is to correct the imbalance of power between the food industry and its workers that “allowed for the abuses that we were facing.”

In 2011, the CIW launched the Fair Food Program (FFP), an agreement between the CIW, farms and retail food companies that pledge to purchase produce only from growers who agree to a code of conduct with enforceable consequences, ensuring the civil rights of farmworkers are protected. Megabrands such as McDonald’s and Walmart are among the participating buyers, and the group is targeting holdouts: on March 10–12, the CIW will lead a series of marches through New York City to put pressure on Wendy’s to join.“We realized that if we were going to actually address the poverty and the abuses on the farm,” says Greg Asbed, 56, another co-founder, “we’d have to look beyond the farm for the answer.” —Madeleine Carlisle